The Missoula flood shaped Washington’s wine growing region

Washington’s motto is the “perfect climate for wine.” With ideal topography, dynamic geologic history, and 60,000 acres planted to wine grapes, there’s a lot that is “perfect.” The state’s largest AVA, the Columbia Valley AVA, encompasses more than 11 million acres of land suitable for wine grapes. This entire area was affected by one of the most unique events in the Pacific Northwest’s geologic history, the Missoula Floods.

Glacial Lake Missoula

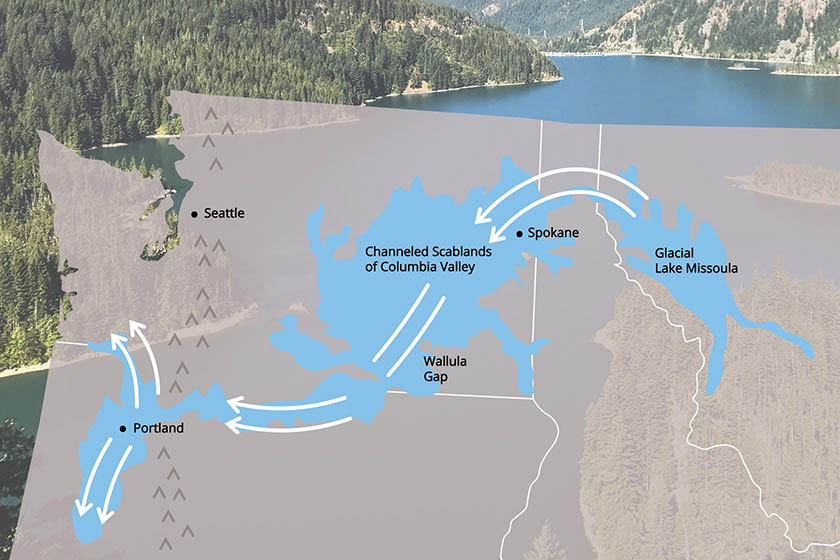

During the last period of continental glaciation, ice blocked and dammed the Clarks Fork River in western Montana, forming an enormous lake named glacial Lake Missoula. With an estimated 7800 square kilometers, the lake proceeded to fill, and the ice dam failed multiple times in at least 4 cycles between 18,000 and 12,000 years ago. Catastrophic flood waters raced across eastern Washington following the ancestral Columbia River valley into Oregon and extending into the Pacific Ocean. In some floods, the water volume was roughly equivalent to 10 times the combined volume of all current rivers around the world. (The Geological Society of America Field Guide 15, K. Pogue, 2009)

Flood deposits and wind blown loess

The flooding water removed any existing topsoils formed after the previous flood, gouged deep grooves into the underlying basalts, and carried large rocks and debris for hundreds of miles. The torrent slowed in a few areas like the Wallula gap allowing the water to pool and, in this calmer environment, deposited slack water sediments (Touchet Beds). These slack water deposits created a stack of graded beds with each successive flood.

Between flood events, the area was blanketed with loess, fine-grained wind-blown (eolian) silts, and sand derived from the mudflats of the earlier deposits’ slack water sediments. The loess was deposited throughout the region, only to be completely eroded or thickened in the next round of floods.

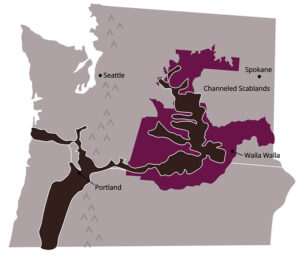

Soil Map (Washington Wine Commission)

The Missoula Floods affected many of the Columbia Valley landforms and soils and thereby the success of the wine-growing region. The large floods generated accumulations of sediment and subsequently removed all or part of those sediments and gouged out the underlying bedrock from vineyard areas. Deep, well-drained soils allow vines to develop deep and strong root systems, such as in the Yakima Valley. In areas where the floods removed large portions of the sediments, leaving thin soils, growing vines will change from the continental rocks overlain by flood-derived sediments to the harder basaltic rocks below. Water availability is likely to become more difficult for those vines as well.

Ultimately for the wine drinker, this dramatic story has left a vineyard scape that is a variable and exciting home for both red and white grapes and produces wines from easy-drinking to powerful and long aging for the glass.

Hero image: Extent of the Missoula Floods (Washington Wine Commission)